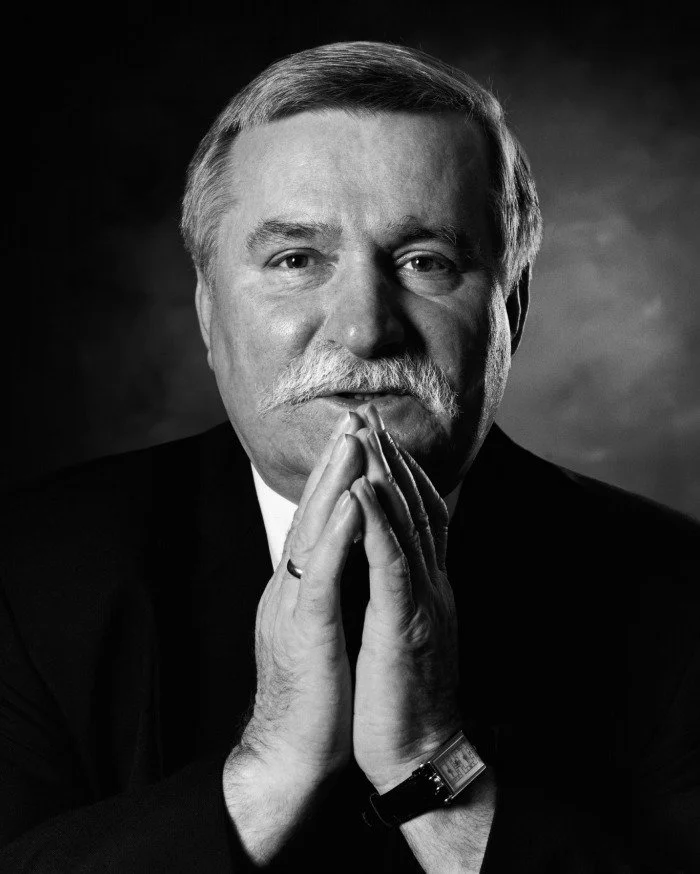

Lech Walesa, 2001

Lech Wałęsa was born September 29, 1943, in the Polish village Popowo, between the cities of Bydgoszcz and Warsaw, during the Nazi occupation. His father Bolesław Wałęsa, a carpenter, was taken to a forced labor camp where he remained until the end of the war. Bolesław died soon after returning to his family, and Lech was raised by his mother, Feliksa Wałęsa, until he attended vocational school to become an electrician.

Lech Wałęsa’s work in labor justice started in the city of Gdańsk in the Gdańsk Shipyard (Stocznia Gdańska), which was known as Lenin Shipyard until 1989. After starting work there in 1967 as an electrician, he began to organize his fellow laborers, which culminated in a strike in the shipyard in 1970 to protest a government decree raising food prices. Law enforcement mercilessly cracked down on the strikers, which led to the deaths of 39 workers. This brutal outcome was a catalyst for Wałęsa, who threw himself into organizing dissident labor unions. This often came at the cost of both his employment and his personal security, because other sites would not hire an illegal union organizer. His dogged and consistent leadership as a unionizer in the 1970s led him to the role of strike leader in the August 1980 Gdańsk Shipyard protest1, which shaped the history of Poland, the Soviet Union, and the world.

In his “leap over the fence” and iconic speech on top of a bulldozer at the shipyard, Wałęsa began to build a strong, collaborative, nonviolent network of striking workers across the nation, called the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee. After 17 days of striking, the Committee was successful, and Wałęsa signed an agreement with the government that gave workers the right to strike and permitted them to form an independent trade union. Wałęsa and his collaborators then converted the Strike Committee into the union known as Solidarity (Solidarność). Embraced by the new Polish pope, Pope John Paul II, as well as the International Labor Organization, Wałęsa had a lot of hope for the growth of the movement. However, fearing the increased threat to their power, Poland’s Communist government retaliated. In 1981, they2 declared martial law and incarcerated Wałęsa and Solidarity’s other leaders for 11 months. Though Wałęsa was released and returned to employment at the Gdańsk Shipyard in 1982, the government outlawed Solidarity.

Throughout the 1980s, Wałęsa continuously put himself at risk to campaign for improved labor rights. He maintained an underground network for the now illegal Solidarity Movement and instigated more strikes and acts of resistance. Although he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1982, the Polish government denigrated his award in the press. Wałęsa feared that if he accepted it, the government would imprison him or refuse to allow him back into the country, so his wife accepted the award on his behalf.

In 1989, after years of resistance, the Polish government began negotiations with political activists in Poland, including Solidarity leaders, for labor and voting rights. Wałęsa campaigned around the country for support for these negotiations, which lasted throughout the year. At the conclusion of the negotiations, the government agreed to reestablish Solidarity and make provisions for semi-free elections. This allowed the Solidarity Citizens’ Committee, an advisory body in name, to succeed as a bona fide political party, gaining a large number of seats in Poland’s legislature3. Wałęsa campaigned around the country for Solidarity’s candidates, using his status as an iconic figure of the movement. His efforts led to the formation of a coalition government for Poland – the first non-Communist government in decades.

In 1990, he became the first democratically elected president of Poland, and used his new position to set in motion the ‘opening’ of Poland, making the country a free market economy. He believed that exposing Poland to the forces of globalization would aid the country’s rebirth, something he noted later during his Pacem in Terris acceptance speech.

He also led the charge to add Poland to the North American Treaty Organization (NATO), another gesture of his intent to collaborate with the non-Soviet world. Though the country was not approved for membership until 1999, Wałęsa did much of the early diplomatic groundwork, despite the restrictions and dangers posed by the Warsaw Pact; military structures of the pact fell apart in 1991, but Russian troops remained in Poland until 1992. Wałęsa remained president until 1995, when he lost reelection to the center-left candidate, Aleksander Kwaśniewski. After his presidency, Wałęsa continued to promote his ideals, founding the Lech Wałęsa Institute to advance democracy and the Polish way toward freedom. He continues to travel the world and speak about the concept of solidarity, as well as economic development in the changing world.

In 2001, Lech Wałęsa became the 31st recipient of the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award, presented by Bishop William Franklin, following Wałęsa’s commencement address to the graduating class of St. Ambrose University of Davenport.

Wałęsa, a powerful orator, has continued to inspire since his stirring bulldozer speech which ignited the 1980 labor strikes and marked the founding of Solidarity. He dedicated himself to campaigning and leading protests around the country until the movement had enough strength to demand free elections. Throughout his life and even after his Presidency, he dedicated himself to worker’s rights and freedom, saying in one of his many speeches “We hold our heads high, despite the price we pay, because freedom is priceless.” His methods of peaceful protest and persistent resistance brought much-needed change to Polish society, and quickened the decline of Soviet control throughout Eastern Europe. His legacy is one of peace, resistance, and commitment to democracy.

Elliot Kiley Modzelewski

Notes 1. The 1980 Shipyard protest was also sparked by economic conditions, including prohibitive increases in food prices. 2. General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who had previously made a show of collaborating with Wałęsa and Solidarity, was the one who declared martial law. From 1981 to 1989, he was the de facto leader of Poland. 3. Poland’s legislature is bicameral, composed of the lower house (the Sejm) and the upper house (the Senate).